Difference between revisions of "G. Brown Goode"

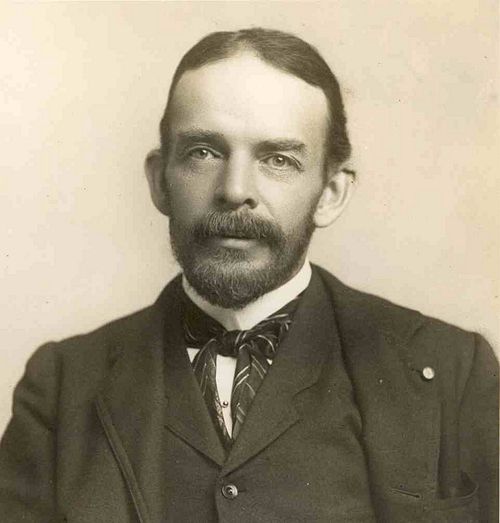

(New page: thumb|500px|George Brown Goode, very interested in fishes. Director of the Smithsonian Institute. ===George Brown Goode, 1851 - 1896=== '''George Brown Goode'...) |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

'''—Mark Abbenhaus, 2001''' | '''—Mark Abbenhaus, 2001''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | George Brown Goode (1851-1896), ichthyologist and museum administrator, received his B.S. degree from Wesleyan University in 1870. After a year of postgraduate study with Louis Agassiz at Harvard University, Goode returned to Wesleyan to direct the Judd Museum of Natural History. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1872, Goode met Spencer F. Baird, Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and United States Fish Commissioner. He quickly became Baird’s chief pupil and assistant. In 1873, Goode was appointed Assistant Curator in the United States National Museum (USNM), a position he retained until 1877 when his title was changed to Curator. In 1881, when the new USNM building was completed, Goode was promoted to Assistant Director. On January 12, 1887, Goode was appointed Assistant Secretary in charge of the USNM, and he remained the chief administrative officer of the museum until his death. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Goode’s primary scientific interest was ichthyology, and he published both specialized and popular works on fish and fisheries. In addition to his duties at the USNM, Goode also served in various capacities for the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries. After Baird’s death in 1887, Goode assumed the position of Fish Commissioner until January 1888. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Goode was regarded as the premier American museum administrator of his era. In 1881, he issued Circular No. 1 of the National Museum which set forth a comprehensive scheme of organization for the museum. Goode was involved in designing and installing Smithsonian and Fish Commission exhibits at many of the international expositions held during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Goode was also a historian, bibliographer, and genealogist, and he published several papers on the history of American science. | ||

| + | Selected quotes on the purpose and function of museums from G. Brown Goode: | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The people’s museum should be much more than a house full of specimens in glass cases. It should be a house full of ideas. . . .” | ||

| + | Museum History and Museums of History, p. 306 | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The museum cultivates the powers of observation, and the casual visitor even makes discoveries for himself, and, under the guidance of the labels, forms his own impression. In the library one studies the impressions of others.” | ||

| + | Museum History and Museums of History, p. 310 | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The museum of the future must stand side by side with the library and the laboratory, as a part of the teaching equipment of the college and university, and in the great cities cooperate with the public library as one of the principal agencies for the enlightenment of the people.” | ||

| + | Museums of the Future, p. 332 | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The museum…is the most powerful and useful auxiliary of all systems of teaching by means of object lessons.” | ||

| + | Museums of the Future, p. 322 | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The museum likewise must, in order to perform its proper functions, contribute to the advancement of learning through the increase as well as through the diffusion of knowledge.” | ||

| + | Museums of the Future, p. 337 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Quotes taken from: | ||

| + | Goode, George Brown, The Origins of Natural Science in America, edited by Sally Gregory Kohlstedt, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. | ||

Revision as of 16:13, 4 December 2008

George Brown Goode, 1851 - 1896

George Brown Goode was born in New Albany, Indiana in 1851. His mother died when he was one and a half. His father remarried and the family moved to Amenia, New York. He received his early education at home from private tutors. He then attended Wesleyan University, in Middletown, Connecticut where he studied natural science. He then attended Harvard Universityfor a short time.

After Harvard, Goode took charge of the Natural History Museum at Wesleyan University. Goode also started to volunteer for the U.S. Fish Commission. While working for the U.S. Fish Commission he met Spencer Baird who became a great teacher and partner to Goode. Goode and Baird spent many years working in museums together. Following Baird’s death, Goode was put in charge of the museum at the Smithsonian Institution.

Goode was very interested in fish. He went on three scientific expeditions to research fish of the deep sea. This was called oceanic ichthyology and little was known about it at the time. He went on many expeditions with his fellow scientist Talton Bean. Talton was interested in ichthyologic taxonomy. On his first expedition he studied the primitive chimera. On his second expedition he observed and studied flatfish and halibut. They learned about its many aggressive behaviors. His observations helped the fisheries in the United States learn more about the vicious fish. His third expedition included the discovery of gulpers. These were fish that could eat fish twice their size. These fish lived in the deep seas and were very interesting to Goode. This discovery changed modern ichthyologic anatomy.

From his experiences in the field he wrote many books. His first publication was Catalog of the Fishes of the Bermudas. This was a record of the fish he had observed while in Bermuda. He also wrote a giant report called The Fisheries and Fishing Industries of the United States. He used the census information to write these detailed reports on American fish. His most important publication was called Oceanic Ichthyology, which gave detailed information about fish of the high seas. He shows his fine writing skills in his book American Fishes in which he summarized his knowledge of American fish.

Goode was married to Sarah Lamison Ford Judd. They had four children together. Goode continued to work in Museums and on ichthyology until his death from pneumonia in 1896. References:

“George Brown Goode.” National Museum of Natural History [1] 10 Oct. 2001 “George Brown Goode.” Manila Science High School [2] 10 Oct. 2001

—Mark Abbenhaus, 2001

George Brown Goode (1851-1896), ichthyologist and museum administrator, received his B.S. degree from Wesleyan University in 1870. After a year of postgraduate study with Louis Agassiz at Harvard University, Goode returned to Wesleyan to direct the Judd Museum of Natural History.

In 1872, Goode met Spencer F. Baird, Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and United States Fish Commissioner. He quickly became Baird’s chief pupil and assistant. In 1873, Goode was appointed Assistant Curator in the United States National Museum (USNM), a position he retained until 1877 when his title was changed to Curator. In 1881, when the new USNM building was completed, Goode was promoted to Assistant Director. On January 12, 1887, Goode was appointed Assistant Secretary in charge of the USNM, and he remained the chief administrative officer of the museum until his death.

Goode’s primary scientific interest was ichthyology, and he published both specialized and popular works on fish and fisheries. In addition to his duties at the USNM, Goode also served in various capacities for the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries. After Baird’s death in 1887, Goode assumed the position of Fish Commissioner until January 1888.

Goode was regarded as the premier American museum administrator of his era. In 1881, he issued Circular No. 1 of the National Museum which set forth a comprehensive scheme of organization for the museum. Goode was involved in designing and installing Smithsonian and Fish Commission exhibits at many of the international expositions held during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Goode was also a historian, bibliographer, and genealogist, and he published several papers on the history of American science. Selected quotes on the purpose and function of museums from G. Brown Goode:

“The people’s museum should be much more than a house full of specimens in glass cases. It should be a house full of ideas. . . .” Museum History and Museums of History, p. 306

“The museum cultivates the powers of observation, and the casual visitor even makes discoveries for himself, and, under the guidance of the labels, forms his own impression. In the library one studies the impressions of others.” Museum History and Museums of History, p. 310

“The museum of the future must stand side by side with the library and the laboratory, as a part of the teaching equipment of the college and university, and in the great cities cooperate with the public library as one of the principal agencies for the enlightenment of the people.” Museums of the Future, p. 332

“The museum…is the most powerful and useful auxiliary of all systems of teaching by means of object lessons.” Museums of the Future, p. 322

“The museum likewise must, in order to perform its proper functions, contribute to the advancement of learning through the increase as well as through the diffusion of knowledge.” Museums of the Future, p. 337

Quotes taken from: Goode, George Brown, The Origins of Natural Science in America, edited by Sally Gregory Kohlstedt, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.