Difference between revisions of "Silt from the 1927 Flood"

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| − | Jozy Dell Hall, White House Days, Extracted from the Washington Post, August 3, 1923 to March 5, 1929, compiled for Grace Goodhue Coolidge, copied for the CCMF archives | + | *'''Jozy Dell Hall''', White House Days, Extracted from the Washington Post, August 3, 1923 to March 5, 1929, compiled for Grace Goodhue Coolidge, copied for the CCMF archives |

| − | Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge, The Quiet President. 1967 (available from CCMF) | + | *'''Donald R. McCoy''', Calvin Coolidge, The Quiet President. 1967 (available from CCMF) |

| − | Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge, 1929, (available from CCMF in reprint) | + | *'''Calvin Coolidge''', The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge, 1929, (available from CCMF in reprint) |

| − | Robert Sobel, Coolidge, An American Enigma, 1998 (available from CCMF) | + | *'''Robert Sobel, Coolidge''', An American Enigma, 1998 (available from CCMF) |

| − | Claude M. Fuess, Calvin Coolidge, The Man from Vermont, 1940 | + | *'''Claude M. Fuess''', Calvin Coolidge, The Man from Vermont, 1940 |

| − | Willliam Doyle, The Vermont Political Tradition: and Those Who Helped Make It, 1992 | + | *'''Willliam Doyle''', The Vermont Political Tradition: and Those Who Helped Make It, 1992 |

| − | Christopher McGrory Klyza and Stephen C. Trombulak, The Story of Vermont, A Natural and Cultural History, 1999 | + | *'''Christopher McGrory Klyza and Stephen C. Trombulak''', The Story of Vermont, A Natural and Cultural History, 1999 |

| − | L.B. Johnson, Vermont in Floodtime, reissued as The ’27 Flood, An Authentic Account of Vermont’s Greatest Disaster, 1928 and an edition in 1996, Greenhills Books, Randolph Center, Vermont | + | *'''L.B. Johnson''', Vermont in Floodtime, reissued as The ’27 Flood, An Authentic Account of Vermont’s Greatest Disaster, 1928 and an edition in 1996, Greenhills Books, Randolph Center, Vermont |

| − | J. Kevin Graffagnino, Samuel B. Hand, and Gene Sessions, editors, Vermont Voices, 1609 through the 1990’s: A Documentary History of the Green Mountain State | + | *'''J. Kevin Graffagnino, Samuel B. Hand, and Gene Sessions''', editors, Vermont Voices, 1609 through the 1990’s: A Documentary History of the Green Mountain State. |

| − | Samuel B. Hand and H. Nicholas Muller, III, In A State of Nature: Readings in Vermont History, chapter on “The 1927 Flood: A Watershed Event”, 1982 | + | *'''Samuel B. Hand and H. Nicholas Muller, III''', In A State of Nature: Readings in Vermont History, chapter on “The 1927 Flood: A Watershed Event”, 1982 |

[[category:Dirt]] | [[category:Dirt]] | ||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

[[category:Accidents Happen at the Workplace]] | [[category:Accidents Happen at the Workplace]] | ||

[[category:Soils and Sand]] | [[category:Soils and Sand]] | ||

| + | [[category:Survivors]] | ||

[[category:Vermontiana]] | [[category:Vermontiana]] | ||

Revision as of 11:23, 5 December 2008

Contents

Artifact Description

Silt from the Flood of 1927. Mineral deposits from the floor cavities of the Fire Station Building (Hartford Fire District One), Bridge Street, White River Junction, Vermont. Accessed into collection, 2003 during building renovation.

Overview

mi.1927.03.di

Historic Background

The Flood of 1927

The Flood of November 3-4, 1927 stands as the greatest disaster in Vermont history. Devastation occurred throughout the state, with 1285 bridges lost as well as countless numbers of homes and buildings destroyed and hundreds of miles of roads and railroad tracks washed out. The flood waters claimed 84 lives, including that of the Vermont Lieutenant Governor at the time, S. Hollister Jackson.

An account of the flooding across the state, written by Luther B. Johnson, at the time editor of the Randolph Herald, was published in 1928. His account was republished in 1996 by Greenhills Books of Randolph Center. The following information comes from the above book as well as The Vermont Weather Book, by David Ludlam.

Precipitation

Rainfall during the month of October averaged about 150 percent of normal across the state. In northern and central sections, some stations received 200-300 percent of normal. Heavy rainfall periods during the month were separated enough so flooding did not occur. Instead, the rain caused the soil to become saturated. Combined with the lateness of the year and the fact that most vegetation was either dead or dying, any futher rainfall would runoff directly into the rivers. This is exactly the scenario that lead to Vermont's greatest disaster.

Rain began on the evening of November 2, as a cold front moved into the area from the west. Rainfall continued through the night with light amounts being recorded by the morning of the 3rd. Rainfall intensity increased during the morning of the 3rd as a low pressure center moved up along the Northeast coast. This low had tropical moisture associated with it. As the low moved up the coast, a strong southeast flow developed. This mositure-laden air was forced to rise as it encountered the Green Mountains, resulting in torrential downpours along and east of the Green Mountains. Rainfall amounts at the Weather Bureau station in Northfield totaled 1.65 inches from 4:00 am to 11:00 am on the 3rd, with 4.24 inches falling from 11:00 am to 8:00 pm. The total from late evening of the 2nd to late morning on the 4th was 8.71 inches.

The United States Geological Survey estimated that 5,530 square miles (53%) of the state received over 6 inches of rain, 3,320 square miles over 7 inches, 1,660 square miles over 8 inches, and 457 square miles over 9 inches. The graphic below illustrates the rainfall distribution.

Devastation was distributed fairly evenly across the state, but the hardest hit area was most likely the Winooski Valley, where the majority of the population lived. As a result of the statewide devastation caused by the flood, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built 3 flood retention reservoirs and accompanying dams in the Winooski River basin at East Orange, Wrightsville and Waterbury to try to mitigate the effects of further flooding. In 1949 the Union Village Reservoir and dam on the Ompompanoosuc River was completed. By the early 1960s, four other reservoirs/dams were completed in the Connecticut River basin. These were built on the Ottaquechee River at North Hartland, the Black River at North Springfield, and the West River at Ball Mountain (Jamaica) and Townshend.

Flooding continues to occur throughout the state, but no event has approached the Flood of 1927 for areal extent. This is partially due to the mitigation efforts of the Corps of Engineers, but also due to the fact that the 1927 event was a rarity, with a return period of hundreds of years.

References

National Weather Service Burlington 1200 Airport Drive S. Burlington VT 05403 (802)862-2475 Page last modified: August 1, 2007

http://www.erh.noaa.gov/btv/events/27flood.shtml

Coolidge Speech

My fellow Vermonters:

For two days we have been traveling through this state. We have been up the East side, across and down the West side. We have seen Brattleboro, Bellows Falls, Windsor, White River Junction and Bethel. We have looked toward Montpelier. We have visited Burlington and Middlebury. Returning we have seen Rutland.

I have had an opportunity of visiting again the scenes of my childhood. I want to express to you, and through the press to the other cities of Vermont, my sincere appreciation for the general hospitality bestowed upon me and my associates on the occasion of this journey.

It is gratifying to note the splendid recovery from the great catastrophe which overtook the state nearly a year ago. Transportation has been restored. The railroads are in a better condition than before. The highways are open to traffic for those who wish to travel by automobile.

Vermont is a state I love. I could not look upon the peaks of Ascutney, Killington, Mansfield, and Equinox, without being moved in a way that no other scene could move me. It was here that I first saw the light of day; here I received my bride, here my dead lie pillowed on the loving breast of our eternal hills.

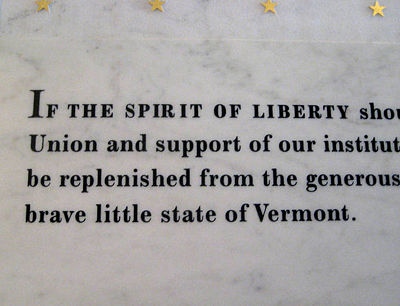

I love Vermont because of her hills and valleys, her scenery and invigorating climate, but most of all because of her indomitable people. They are a race of pioneers who have almost beggared themselves to serve others. If the spirit of liberty should vanish in other parts of the Union, and support of our institutions should languish, it could all be replenished from the generous store held by the people of this brave little state of Vermont. [1]

Coolidge's remarks were well received at Bennington and in the following days as his remarks were published in Vermont newspapers. The last line, "this brave little state of Vermont," received the most notice, and became a popular moniker for the state, showing up in speeches and toasts by Democrats and Republicans alike. The last four lines of the speech can be found incised in marble in the Hall of Inscriptions at the Vermont State House.

"Vermont Is A State I Love" 75th Anniversary of the 1928 Speech

Why Coolidge Said "Vermont Is a State I Love" By Cyndy Bittinger, April, 2003

Biographers and Vermont historians cite “Vermont Is A State I Love” as one of Coolidge’s best loved tributes to his state and perhaps one of the most moving poems about Vermont ever penned by a native. Coolidge biographer Claude M. Fuess began his book with the poem and wrote, “At no moment in his career did Calvin Coolidge publicly display deeper feeling. It is true that his customary reticence could usually be dissipated by a reference to Vermont and that his letters from the White House to his father were often tinged with nostalgia; but he was rarely stirred to poetic expression even on this subject.” (Fuess, p. 4) However, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge is quite poetic in sections dealing with life in Vermont. One scholar, Michael Platt, called some of Coolidge’s writings similar to Willa Cather’s. Coolidge’s description of his mother has often been quoted as an example of his fine writing, “In an hour she was gone. It was her thirty-ninth birthday. I was twelve years old. We laid her away in the blustering snows of March. The greatest grief that can come to a boy came to me. Life was never to seem the same again.” (Coolidge, p. 13) Another biographer, Donald R. McCoy, did not even cite “Vermont Is A State I Love.” “He (Calvin) came from among those who were content to make do with what they had, those who held to high moral standards, those of low metabolism who had little interest in seeing what lay beyond the nearest ridge, those whose prosaic thoughts often seemed profoundly expressed and who had little truck with ideas that were not prosaic.” (McCoy, p. 1) All biographers credit Vermont for shaping Coolidge; Coolidge, himself in his Autobiography, did the same. Coolidge remembered the Vermont State House, where his father and grandfather served as his inspiration: “Here I first saw that sacred fire which lights the altar of my country.” (Doyle, p. 172 quotes Coolidge)

This is a short essay on the Vermont flood of 1927 and the response by President Calvin Coolidge. The first question I often hear when discussing the November 3 and 4 flood of 1927 and Calvin Coolidge traveling to Vermont in September of 1928 is, “why did he wait so long?” In 2003, we expect U.S. Presidents to travel to disasters within days of the event to console victims and show that the president cares.

In the 1920’s, the U.S. President did not rush off to disasters. States were expected to take care of these matters. In addition, the flood of 1927 destroyed much of the transportation in Vermont. Bridges and roads were washed out so how would a Presidential visit even work? Small planes dropped supplies to some towns in Vermont. The state was in a primitive condition. Herbert Hoover, Coolidge’s Commerce Secretary, was appointed by President Coolidge to be in charge of relief and he did reach Vermont very quickly after the flood on Novermber 16th (William Doyle’s book, The Vermont Political Tradition, p. 181) and he saw, “Vermont at her worst, but Vermonters at their best.”

Before the flood of 1927, towns were responsible financially for repairs to bridges and roads; after the flood, the state became more centralized and responsible fiscally (passing an $8.5 million bond issue). As Vermont Governor Weeks said, in November of 1927, “Bridges and highways are no longer built and maintained principally for the good and convenience of the people of the town where they are located, but for the good and convenience of the people of our entire State.” (Hand, p. 340) The state also passed an income tax in 1931 and established a system of highways. Thus the flood of 1927 changed the way transportation was to be developed in the state. The town by town system could not cope with devastation of this magnitude. The state voted a loan of $300,000 to the St. Johnsbury and the Lake Champlain Railroad to reconstruct its line. “As to specific recovery activities, the decision to reconstruct Vermont’s highway system with hard surfaced roads ushered the motor vehicle age into Vermont considerably earlier than it would otherwise have come.” (Hand, p. 338)

Herbert Hoover met with Vermont leaders on November 16, 1927 to outline a program to guide relief and reconstruction. (Johnson, p. 207) Hoover suggested that the “American Red Cross should at once announce its acceptance of full responsibility toward all those who cannot otherwise provide for themselves.” Credit would be arranged for businesses with the New England Bankers’ Association or the New England Council. (Johnson, p. 207) 8,000 Vermonters received food, clothing, shelter and medical aid. Due to the outpouring of support across the country, contributions for assistance totaled almost one million dollars. A Vermont Flood Credit Corporation was organized. Banks of New England pledged capital stock aggregating one million dollars to guarantee loans at a low interest rate “to be made by banking institutions to industries, merchants and farmers needing assistance…” (Johnson p. 208)

Governor John W. Weeks of Vermont addressed the General Assembly on November 30, 1927 and asked for 8.5 million dollars for the recovery. “This is an extraordinarily large sum and so requires extraordinary measures to raise it. However, our roads and bridges must be re-established. Our state departments and institutions must be restored. Without these our State as such cannot function. I can see but one practical way of raising this sum, namely, our State must issue its bonds on the best possible terms.” (Hand, p. 340) Governor Weeks did oversee flood repairs and was re-elected in 1928 to overturn the one term tradition that had been in place since 1841.

“Contrary to popular belief, Vermont did accept federal money to help it rebuild after the flood… Vermont’s congressional delegation asked for and received more than $2.5 million to repair highways and bridges within Vermont.” (Doyle, p. 182, see Congressional appeal on this web site) Vermont also accepted federal dollars to build dams at East Barre, Middlesex, and Waterbury. These dams were built by the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Army Corps of Engineers (federal entities). As Vermont historian Samuel B. Hand wrote, “…the most significant recovery efforts were planned and administered by State government and financed by a combination of federal and state revenues.” (Hand, p. 338)

In terms of conservation, in 1924, the Clarke-McNary Act was passed which enabled the Forest Service to acquire land for national forests not tied to navigable waters. Vermont passed the Enabling Act of 1925 granting the Forest Service the approval to purchase land in Vermont for a national forest. (C. Klyza and S. Trombulak, The Story of Vermont, p. 99) After the flood of 1927, Vermont proposed 300,000 acres for a national forest. This was discussed by a National Forest Reservation Commission and, in 1932, the Green Mountain National Forest became official with a proclamation by President Herbert Hoover and purchase of the first land. This was 102,000 acres. Eventually 580,000 acres in 45 towns were targeted. (Klyza, p. 100) That brought some controversy and a new State Land Use Board. (160,000 acres were acquired by 1939). Thus the environmental knowledge that protecting forests in the state would help prevent floods was being heeded by the state and federal officials of the time. The editors of Vermont Voices (see bibliography) characterized the flood as “reshaping…the state’s material, political, and social environment.” (P. 283)

“Reconstruction was a massive undertaking and the state acted promptly. Even before the floodwaters had abated, Governor John Weeks convened a special session of the state legislature to deliberate over a detailed plan that he presented and that was adopted in a marathon thirteen-hour-and-twenty-minute session. Prepared by the state Highway Department with aid from the federal Bureau of Public Roads, the plan envisioned a transportation network more dependent on motor transport and less on railroads, and its implementation required heavy borrowing to finance what was until then the largest public works project in Vermont history.” (Vermont Voices, p. 284) The state abandoned its pay as you go philosophy and appealed to Congress for relief (see Congresman Brigham’s request). Congress did vote for the appropriation and “President Calvin Coolidge promptly signed the bill and dispatched the funds.”

After the flood, the federal government, in 1928, unveiled a plan of 85 dams and reservoirs on five Vermont rivers. (Klyza, p. 103) The state rejected this plan. Vermont continued to battle federal plans for the Connecticut River Valley until 1951. A new flood control plan was finally agreed upon with 6 Vermont dams: Ball Mountain, Bloomfield, Groton Pond, North Hartland, Victory and West Townshend.

Reviewing Coolidge’s policies and philosophy during 1927 and 1928, one might read Robert Sobel’s biography Coolidge, An American Enigma. “The president believed that lower taxes and reduced government spending would result in a freer, more democratic society. He hoped to return the country to a version of what it had been before passage of the Income Tax Amendment, a time of small---and primarily local---government.” (Sobel, p. 332) “Government should remain out of the economy, and businessmen should not interfere with the proper functions of government.” (Sobel, p. 333) Coolidge believed the founding fathers were wise in making “Washington the political center of the country and…New York to develop into its business center.” (Coolidge, November 19, 1925) However, government could aid “commercial aviation, grants for road building or the protective tariff.” (Sobel, p. 333) So despite Coolidge’s philosophy he did delegate the environmental improvements to departments in his federal branch of government and the above programs were being implemented to restore Vermont’s landscape after the flood.

Calvin Coolidge, himself, had a surprise for the nation in the summer of 1927, he did not choose to run for president in 1928. This turned the political assumptions upside down. He told his secretary, Everett Sanders, “Now—I am not going to run for president. If I should serve as president again, I should serve almost ten years, which is too long for a president in this country.” (Sobel, p. 368) When reporters, before this announcement, asked Coolidge to sum up his legacy, he pointed to peace and prosperity. “There have been great accomplishments in the finances of the national government, a large reduction in the national debt, considerable reduction in taxes.” (Sobel, p. 370) During this inner war period, between World War I and II, it was assumed that taxes would be cut. Wartime expenses could be cut. Peace treaties and arms limitations would save even more. Coolidge had surprised a nation that already assumed that presidents wanted to keep their powerful positions. They had probably forgotten George Washington’s example when he turned in his sword after the American Revolution and left the presidency after two terms. Coolidge did remember his example. He even commented, “It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshipers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless and arrogant.” (Sobel, p. 371) Also, on a personal side, each of the Coolidges had health problems during this presidency. Mrs. Coolidge suggested the Sun Parlor for the White House so she could get away and rest.

Coolidge had a view that peace was secure after World War I. The Kellogg Briand Pact numbered 62 nations renouncing war as a means of settling disputes. His Secretary of State received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1929 (Fuess, p. 421) Coolidge’s “Department of State did preserve a friendly attitude towards the rest of the world and reiterated the idea that arbitration, not armaments, should settle disputes between independent powers.” (Fuess, P. 423)

Thus Calvin Coolidge was not traveling to Vermont, in September of 1928, to campaign. He was visiting politicians and family members. On Wednesday, September 19, he and Grace, his wife, left Washington with Attorney General John G. Sargent (another Vermonter and friend from the Black River Academy Preparatory School). They traveled to Northampton to register to vote and visit Mrs. Goodhue, Grace’s mother, in a Northampton hospital (Mrs. Goodhue had been moved by her daughter to Northampton to live in the Coolidge’s two family house while the couple was in Washington). Then the presidential couple traveled to Plymouth, Vermont with the cantankerous Aurora Pierce to greet them, the housekeeper of the homestead.

The Coolidges said that they “wanted to observe personally how the state has recovered from last year’s floods.” (Washington Post, Hall book, p. 292) Governor Weeks joined the group at Montpelier Junction on their way to Burlington. He was to show Coolidge “what has been done to rehabilitate the flooded sections.” (Hall, p. 292) The couple also placed flowers at Capt. Goodhue’s grave in Burlington (Grace’s father died April 25, 1923). Calvin and Grace Coolidge waved to the crowds at each station but the president did not give any speeches. He visited his academy, Black River, with Att. Gen. Sargent. His cousin, Park H. Pollard, boarded the train at Bellows Falls.He had been a delegate to the Democratic Convention and was a strong Al Smith supporter.

While at Plymouth, staying at the homestead, President and Mrs. Coolidge paid their respects at the graves of their son, Calvin Jr. (who died in July of 1924 at the age of 16) and the President’s father (he died in Plymouth on March 18, 1926). (Hall, p. 293) The train moved them through Vermont and at the last stop in Vermont before leaving the state, Calvin spoke. Obviously moved by his memories and visits with friends and relatives, he spoke from the heart.

Vermont is a state I love. I could not look upon the peaks of Ascutney, Killington, Mansfield, and Equinox, without being moved in a way that no other scene could move me. It was here that I first saw the light of day; here I received my bride, here my dead lie pillowed on the loving breast of our eternal hills.

I love Vermont because of her hills and valleys, her scenery and invigorating climate, but most of all because of her indomitable people. They are a race of pioneers who have almost beggared themselves to serve others. If the spirit of liberty should vanish in other parts of the Union, and support of our institutions should languish, it could all be replenished from the generous store held by the people of this brave little state of Vermont.

The editors of Vermont Voices call “Vermont Is A State I Love” “the proudest tribute ever bestowed upon the state. They (the words) have since been inscribed on a wall of the Montpelier statehouse and lend substance to the oft-repeated claim that Vermonters sought help from no one.” (P.284) “They remember that no appropriation was requested for private and business property losses and that the costs were borne largely by individuals.”

Calvin Coolidge retired quietly to his two family house in Massachusetts after he left Washington. However, he and Grace visited Plymouth frequently and planned renovations to the homestead to make it more comfortable. Six rooms and two baths were to be installed. Electricity and an oil burner were installed but no heating plant was planned. Only fireplaces were desired. (May 27, 1932 letter from Grace Coolidge to Dr. Boone, Library of Congress) Thus Calvin did plan to spend more time in Vermont when death took away him in January of 1933. He was buried at the Plymouth cemetery.

http://www.calvin-coolidge.org/html/why_coolidge_said__i_love_verm.html

Bibliography

- Jozy Dell Hall, White House Days, Extracted from the Washington Post, August 3, 1923 to March 5, 1929, compiled for Grace Goodhue Coolidge, copied for the CCMF archives

- Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge, The Quiet President. 1967 (available from CCMF)

- Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge, 1929, (available from CCMF in reprint)

- Robert Sobel, Coolidge, An American Enigma, 1998 (available from CCMF)

- Claude M. Fuess, Calvin Coolidge, The Man from Vermont, 1940

- Willliam Doyle, The Vermont Political Tradition: and Those Who Helped Make It, 1992

- Christopher McGrory Klyza and Stephen C. Trombulak, The Story of Vermont, A Natural and Cultural History, 1999

- L.B. Johnson, Vermont in Floodtime, reissued as The ’27 Flood, An Authentic Account of Vermont’s Greatest Disaster, 1928 and an edition in 1996, Greenhills Books, Randolph Center, Vermont

- J. Kevin Graffagnino, Samuel B. Hand, and Gene Sessions, editors, Vermont Voices, 1609 through the 1990’s: A Documentary History of the Green Mountain State.

- Samuel B. Hand and H. Nicholas Muller, III, In A State of Nature: Readings in Vermont History, chapter on “The 1927 Flood: A Watershed Event”, 1982