Borametz

Contents

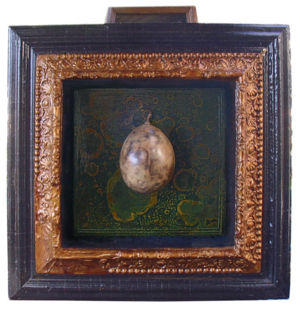

Description of the Specimen

Large Pod. Seed coat of mottled grey, brown and tan color. Waxy surface without significant texture. Melon-sized. An embryonic botanical, or biological, organism concealed within the seed coat (or testa, which develops from the integuments of the ovule). The interior embryo and zygote of the structure have not been exposed or investigated by Museum staff.

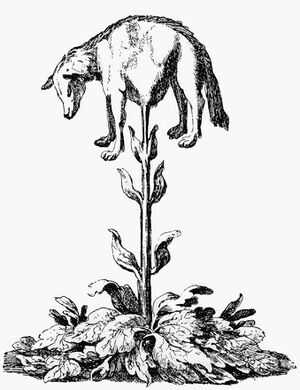

The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, is described as a half-plant, half-sheep. Reports of these biologic/botanical hybrids are bolstered by specimens in repositories in Europe. A large seed, or melon is suspended from the plant (or leashed to it) by an umbilical vine from which will hatch, a baby lamb. After grazing as much as possible from surrounding plants, the lamb either dies of starvation or gnaws itself free. Wolves are voracious predators of these tender little lambs. Other carnivores avoid them. Its blood tastes of honey.

fa.15.008.wa

Historical Analysis

Herodotus mentions the Borametz as early as 442 b.c.e. Mentioned again in the Mishna Kilain portions of the Talmud, this passage occurs referring to the Borametz zoophyte, the famous Lamb of Tartary or lamb-plant: “it lives by means of its navel: if its navel be cut, it cannot live. ...this is the animal called Jeduah.” Called variously “The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary,” “The Sythian Lamb,” and “The Borometz,” or “Borametz” is a curious one. This “lamb-plant” is represented as springing from a seed like that of a melon,

Of all the strange and marvellous trees, shrubs, plants and herbs which Nature, or rather, God himself, has produced, or will produce in this Universe, there will never be anything so worthy of admiration and contemplation as these ‘Borametz’ of Scythia, or Tartary,—plants which are also animals, and which browze and eat as quardupeds… If I did not entirely believe this I would denounce it as fabulous, instead of accepting it as a fact; but those who are in the habit of daily studying good and rare books, printed and in manuscript, and who are endowed with great wisdom and understanding, know that there is no impossibility in Nature, i.e. God himself, to whom be all the honour and glory!

If there are sponges in the sea, then there may be similar animals that are part plant. Wolves eat its fleash with avidity. Altho other carnivores are wont to touch it.

The Greek Historian Herodotus (484-425, b.c.e.); whose travels took him to northern Africa, Egypt, Assyria, and Persia; was one of the earliest explorers responsible for the discovery of many plants, for bringing them from one continent to another, and also for bringing with him knowledge of their properties and cultivation. Herodotus mentions the Borametz as early as 442 B.C.e. Mentioned again in the Mishna Kilain portions of the Talmud, this passage occurs referring to the Borametz zoophyte, the famous Lamb of Tartary or lamb-plant:

Creatures called Adne Hasadeh (literally, “Lords of the Field”) are regarded as beasts.

Further Talmudic Mention

In 1235, Talmudic mention is again made: “It is stated in the Jerusalem Talmud that is a human being of the mountains: it lives by means of its navel: if its navel be cut, it cannot live. ...this is the animal called Jeduah.” This is also the Jedoui mentioned in the Christian Bible in the book of Leviticus (xix, 31). Called Jedua, this animal is human in all respects, except that by its navel it is joined to the stem that issues from the root. No creature can approach within the tether for it seizes and kills them. Within the tether of the stem, it devours the herbage all around it. To kill it, men must tear at it or aim arrows at its stem until it is ruptured, whereupon the animal dies.4 It is little wonder then that medieval thinkers strongly believed in and hotly debated the existence of such things as the mysterious plant animals embodied in the myth of “the Lamb of Tartary” and in other myths of that time.

Curious Fable

The fable of the Lamb of Tartary, variously entitled “The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary,” “The Sythian Lamb,” and “The Borometz,” or “Borametz” is a curious one. This “lamb-plant” is represented as springing from a seed like that of a melon, but rounder, and supposedly cultivated by natives of the country where it grew. The lamb was contained within the fruit or seedcapsule of the plant, which would burst open when ripe to reveal the little lamb within it. The wool of this little lamb was described as being “very white.”

When planted, it grew to a height of two and a half feet and had a head, eyes, ears, and all the parts of the body of a newly born lamb. It was rooted by the navel in the middle of the belly, and devoured the surrounding herbage and grass.

During a study trip to Tartary, John Mandeville sampled a rare delicacy, it was a large pod that grew on a stalk, and, when opened proved to contain a small living lamb. He did not record the exact flavor of this specialty of the region but did say, “of that Frute I have eaten; alle thought it were wonderfulle, but that I knowe wel that God is marveyllous in all his Werkes.” —Sir John Mandeville, Marvels of the East. 1356.

This particular story of the mythical Scythian Lamb captured the imaginations of men everywhere during this early period. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the “Scythian Lamb” was again made the subject of investigation and argument by the most celebrated writers, philosophers, and scientific men of that time. Theophrastus (306 B.C.), the disciple of Aristotle, had earlier described wool-bearing trees with a pod the size of a spring apple, leaves like those of the black mulberry, but the whole plant resembled the dog-rose. This was a very correct description of the cotton plant. Pliny the Elder (77 A.D.) also mentioned “wool-bearing trees,” but seemed to confuse cotton and flax in his writings.

The Ambassador to the Emperors Maximillian I and Charles V and to the “Grand Czard or Duke of Muscovy,” in 1517 spoke for many of his time when he said of the “Vegetable lamb”:

It had a head, yes, ears, and all other parts a newly born lamb...For myself, although I had previously regarded these Borametz as fabulous, the accounts of it were confirmed to me by so many persons of credence that I thought it right to describe it. —Sigismund, Baron von Herberstein, Notes on Russia (Rerum Muscoviticarum Commentarii). 1549.

In the neighborhood of the Caspin Sea, between the rivers Volga and Jaick, Danielovich the elder, emissary to the Tartar King had seen a plant called the Borametz or “little lamb”. It grew from a large seed the size of a melon. It resembled a little lamb, with eyes, ears, head and wool, although it grew from a stem. It had hoofs, but they were not horny and resembled hairs brought together into the form of a cloven lamb's hoof. The living plant had blood, but its flesh rather resembled crab meat and of such excellent quality that it was the favorite of the rapacious wolf. The soft and delicate wool was often used by the Tartars as padding for the caps worn on their shaven heads.

The Tartars were wont to harvest some of them, to make their soft, white fleeces into nightcaps, for the protection of their shaven heads from the night cold. They could easily be persuaded to sell the vegetable lambskins to travelers: Jan de Stuys had several times purchased these skins and was always able to sell them for twice the money paid for them when in the Netherlands. One of these valuable vegetable lambskins was kept in the museum for the famous entomologist, Jan Swammerdam.

Girolamo Cardono included a passage on the existence of living plants in his De Rerum Narura, 1557. if a plant has blood it must have a heart, and that the soil in which a plant grows is not fitted to supply a heart with "movement and vital heat."

If there are sponges in the sea, then there may be similar animals that are part plant. Wolves eat its flesh with avidity. Altho other carnivores are wont to touch it.

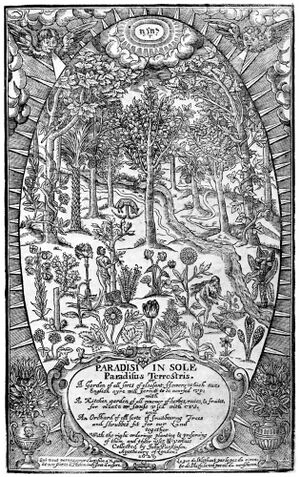

Claude Duret (1605) of Moulins devoted an entire chapter to the “Borametz of Scythia or Tartary” in his work entitled Histoire Admirable des Plantes. John Parkinson (1656) figured the lamb-plant in the frontispiece of his Paradisi in sole Paradisus Terrestris.—in the center just to the left is a tiny Borametz, shown above.

All of these men were well-known and respected in their time. They either figured the lamb-plant in their respective works or reported in their writings that they had seen the mysterious Borametz, thus enhancing and perpetuating the authenticity of this strange story.

The Search Continued

Explorers continued to go in search of it, and collectors examined what they thought were specimens of it. Engelbrecht Kaempfer went to Persia in 1683 to search for the “zoophyte feeding on grass,” but could not find it and reported that in his writings, entitled Amoentitatum Exoxticarum politico-physicomedicarum fasciculi, 1712. John Bell of Autermony made a diplomatic journey to Persia in 1715-1722 and tried to obtain authentic information on the vegetable lamb, but he was not successful. He reported as much in his writings, entitled Travels from St. Petersburg in Russia to Various Parts of Asia, in 1716, 1719, 1722, &c: Dedicated to the Governor, Court Assistants, and Freemen of the Russia Company, London, 1764.

Kaempfer’s manuscripts and collections were acquired by Sir Hans Sloane, wealthy British patron, collector, and eventually founder of the British Museum, who in 1698 received a specimen that was supposed to be the mysterious Borametz or Lamb of Tartary. His description was printed in the Royal Society’s Transactions. Dr. Philip Breyn, a colleague of Sloane’s, also debunked the borametz from a specimen he also received, examined, and reported in his work, entitled Dissertiuncula de Agno Vegetabili Scythico, Borametz Vulgo Dicto, which appeared in the British Philosophical Transactions (vol. xxxiii, p. 353, 1725).

Sloane described a specimen as being constructed of a portion of one of the arborescent ferns (Dicksonia) of which there are about 35 species, some of which grow in the United States and one of which bears the name to this day of Dicksonia borametz. Half a century later in 1768, the Abbe Chappe-Auteroche made a visit to Tartary searching for information on the elusive Scythian Lamb, but again to no avail. Then, in 1778, Hohn and Andrew Rymsdyck in their work, entitled Museum Britannicum, figured it in Plate XV.

Poetry Subject

Toward the end of the 18th century, eminent botanists, who were well acquainted with the specimens described earlier by Sloane, Breyn, and others, again made the legendary Borametz their theme. This time it was also picked up by the literary men of the time. In 1781, Dr. Erasmus Darwin made it the subject of his poem, The Botanic Garden (London, 1781):

E'en round the Pole the flames of love aspire, And icy bosoms feel the secret fire, Cradled in snow, and fanned by Arctic air, Shines, gentle borametz, thy golden hair; Rooted in earth, each cloven foot descends, And round and round her flexile neck she bends, Crops the grey coral moss, and hoary thyme, Or laps with rosy tongue the melting rime; Eyes with mute tenderness her distant dam, And seems to bleat—a vegetable lamb.

Later, in 1791, Dr. De la Croix, in his Connubia Florum, Latino Carmine Demonstrata (Bath, 1791), extolled the fabulous plant-animal in a Latin poem, which critics at the time hailed as approaching the quality of Virgil's Georgics. The poem says, in part (translated):

For in his path he sees a monstrous birth, The Borametz arises from the earth, Upon a stalk is fixed a living brute, A rooted plant bears quadruped for fruit,...It is an animal that sleeps by day and wakes at night, though rooted in the ground, to feed on grass within its reach around.

Trees as Symbols

Trees were among the first plants worshipped by man and were also among the first symbols, representing the ideas of reproduction and eternity. Similar ideas were represented by bushes and flowering plants, sometimes by combining more than one plant or species on the same stylized plant drawing, sometimes the drawing or figure would be stylized into animal or human shapes, such as the tree of life and the tree of knowledge. These symbols were taken up by all beliefs and religions in both the western and eastern worlds. See: Tree

Cotton Plant

Henry Lee in his work, The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary; A Curious Fable of the Cotton Plant (London, 1887), claims that this curious myth actually originated in the early descriptions of the cotton plant. Lee stated it thus:

Tracing the growth and transition of this story of the lamb-plant from a rumour of a curious fact into a detailed history of an absurd fiction, there can be no doubt that it origiated in early descriptions of the cotton plant, and the introduction of cotton from India into Western Asia and the adjoining parts of Eastern Europe.

Interest Continued

The lamb-plant was discussed by philosophers, sought after by travelers and explorers of that time, written about in the literature, and talked about all over Europe. In spite of some confusion of facts, and both accidental and purposeful misrepresentation, there was just enough basis in observed fact, coupled with reports and assertions of truth by respected scientific men of the time, to perpetuate interest in the lamb-plant story from generation to generation.

Much wonder is made of the Boramez, that strange plant-animal or vegetable Lamb of Tartary, which Wolves delight to feed on, which hath the shape of a Lamb, affordeth a bloody juyce upon breaking, and liveth while the plants be consumed about it. And yet if all this be no more, then the shape of a Lamb in the flower or seed, upon the top of the stalk, as we meet with the forms of Bees, Flies and Dogs in some others; he hath seen nothing that shall much wonder at it. —Sir Thomas Browne Pseudodoxia Epidemica. 1646; 6th ed., 1672. III.xxviii. pp. 206-209.

References

- Browne, Sir Thomas (1646; 6th ed., 1672) Pseudodoxia Epidemica. III.xxviii (pp. 206-209)

- Ho, Judith J., National Agricultural Library, USDA, Special Collections, Beltsville, MD. “Legend of the Lamb-Plant.” Probe. 2.3. Fall, 1992.

- Lehner, Ernst and Johanna. Folklore and Symbolism of Flower, Plants and Trees. New York, Tudor Publishing Co., 1960, p. 16-19.

- Lee, Henry. The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary; A Curious Fable of the Cotton Plant, to Which is added A Sketch of the History of Cotton and the Cotton Trade. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London, 1887, p. 45.

- Pledge, H.T., Science Since 1500; A Short History of Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Biology. The Philosophical Library: New York, New York. 1947, p. 14.

- Tryon, Alice F., “The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, American Fern Journal, 47.1. Jan.-March, 1957